Innovation Delivered

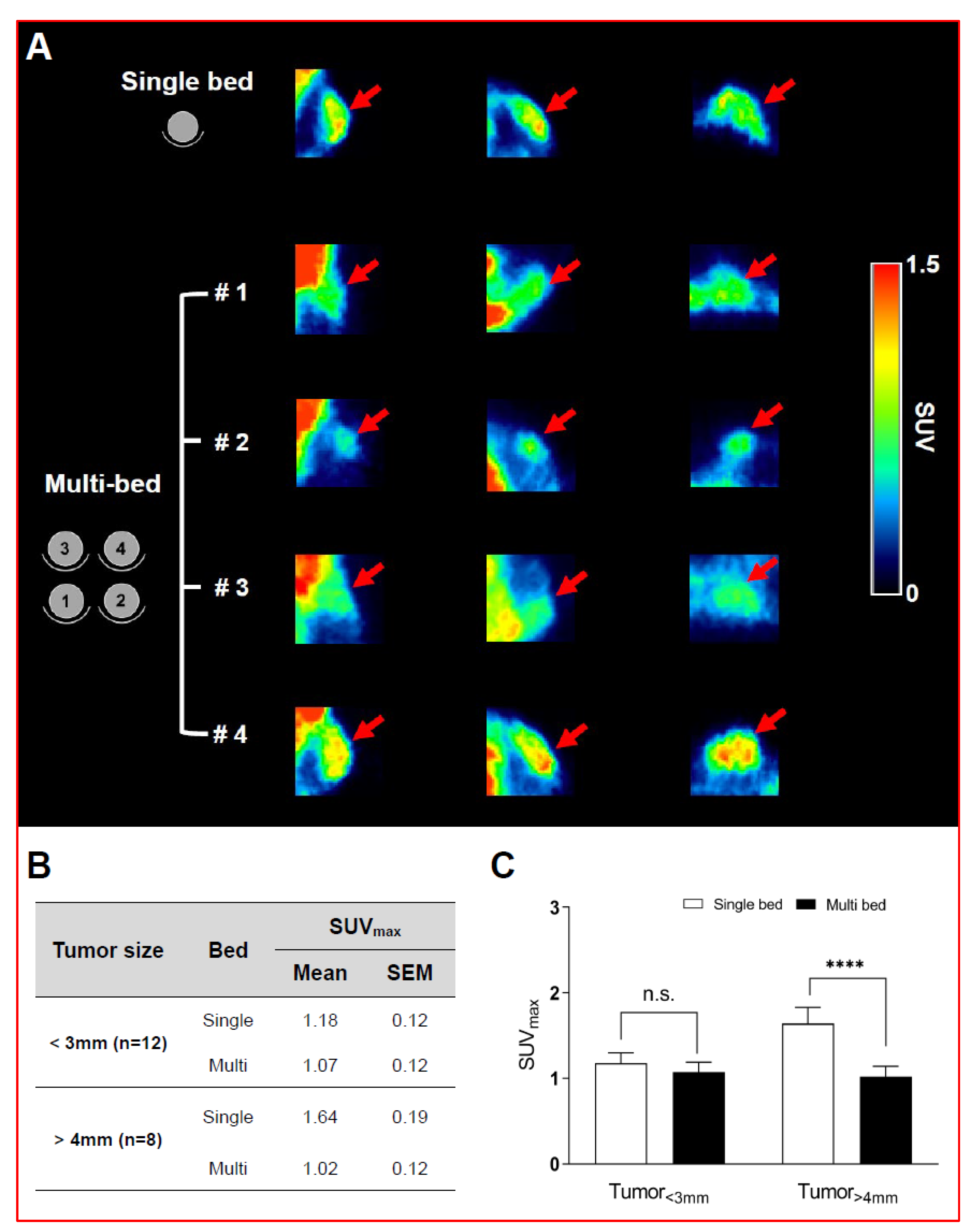

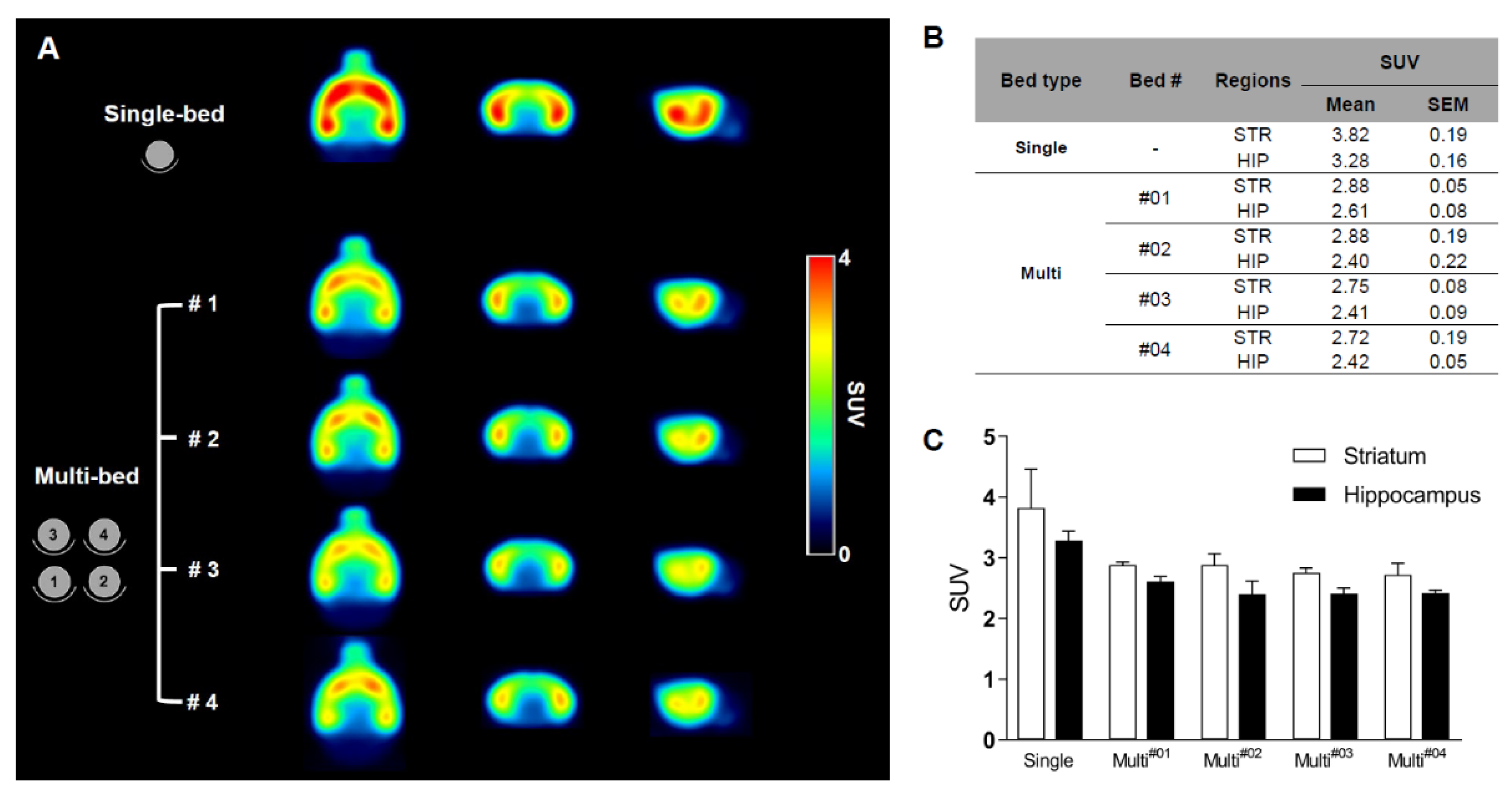

Validation of Image Qualities of a Novel Four-Mice Bed PET System as an Oncological and Neurological Analysis Tool

Kyung Jun Kang1, Se Jong Oh1, Kyung Rok Nam1, Heesu Ahn1,2, Ji-Ae Park1,2, Kyo Chul Lee1, Jae Yong Choi1,2

1Division of Applied RI, Korea Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences, Seoul 01812, Korea

2Radiological and Medico-Oncological Sciences, University of science and technology (UST), Seoul 01812, Korea

https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging7030043

For this purpose, researchers use micro-PET (µPET), which is a small-animal dedicated system. Most µPET vendors provide a single bed, thereby allowing imaging of only a single animal at a time. Large-scale research involving many objects thus requires tremendous time and use of radioactivity.

Recently, Mediso developed a multi-bed system dedicated to the nanoScan scanners with the contribution of Tim Witney and his team at UCL and KCL, where the initial validity for research has been investigated. Greenwood et al. (https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.119.228692) tested the four-bed mouse system using 2-deoxy-2-(18F)fluoro-D-glucose (18F-FDG) in phantom and normal mice and reported a quantitative accuracy similar to that of a single-bed. To date, however, few studies have focused on the validity of oncological and neurological PET imaging of the four-mice bed system.

This study aimed to evaluate the image qualities of oncological and neurological PET imaging using a novel four-mice bed system.

Opioid–galanin receptor heteromers mediate the dopaminergic effects of opioids

Ning-Sheng Cai1, César Quiroz1, Jordi Bonaventura2, Alessandro Bonifazi3, Thomas O. Cole4, Julia Purks5, Amy S. Billing6, Ebonie Massey6, Michael Wagner6, Eric D. Wish6, Xavier Guitart1, William Rea1, Sherry Lam2, Estefanía Moreno7, Verònica Casadó-Anguera7, Aaron D. Greenblatt4, Arthur E. Jacobson8, Kenner C. Rice8, Vicent Casadó7, Amy H. Newman3, John W. Winkelman5, Michael Michaelides2, Eric Weintraub4, Nora D. Volkow9, Annabelle M. Belcher4, Sergi Ferré1

1Integrative Neurobiology Section.

2Biobehavioral Imaging and Molecular Neuropsychopharmacology Unit and.

3Medicinal Chemistry Section, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Intramural Research Program (IRP), NIH, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

4Division of Alcohol and Drug Abuse, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of Maryland, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

5Massachusetts General Hospital, Departments of Psychiatry and Neurology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

6Center for Substance Abuse Research, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, USA.

7Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biomedicine, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

8Drug Design and Synthesis Section, NIDA, IRP, and.

9NIDA, NIH, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

https://doi.org/10.1172/jci126912

Summary

Identifying nonaddictive opioid medications is a high priority in medical science, but μ-opioid receptors (MORs) mediate both the analgesic and addictive effects of opioids. And as possibly everyone knows, the opioid epidemic shows a severe public health crisis worldwide.

Maintenance treatment with the (MOR) agonist methadone is the most highly researched and evidence-based treatment for opioid use disorder. Yet public perception concerning the substitution of illicit drugs (such as heroin) with medication (such as methadone) has led to stigmatized views of maintenance treatment, stalling the advancement of addiction treatment policy and access to medication-based treatments. MOR agonism also offers the most effective treatment for severe pain, making the search for a nonaddictive opioid drug the holy grail of pain research.

The neuropeptide galanin acts as a modulator of neurotransmission in the CNS and the PNS, and It is coexpressed with different neurotransmitters and coreleased by the major ascending noradrenergic, serotoninergic, histaminergic, and cholinergic systems. The authors recently reported the existence of functionally significant heteromers of the MOR and galanin 1 receptor (Gal1R) in the ventral tegmental area that could explain these galanin-opioid antagonistic interactions.

The present study sought to answer 2 main questions that arose from our study of MOR-Gal1R heteromers: (a) What are the mechanisms involved in the interactions between galanin and opioid ligands within the MOR-Gal1R heteromer? and (b) Do these interactions also involve morphine and synthetic opioids, such as methadone or fentanyl, differentially?

Results from nanoScan PET/CT

For the animal experiments, the authors have used a nanoScan PET/CT, which provided high resolution and sensitivity to follow the [18F]FDG uptake in the selected brain regions, and find significant differences after using the below mentioned drugs in rats.

The timeline of the experiment was slightly different from the usual PET/CT scans, as it involved two acquisitions: for the baseline scan, saline was injected i.p. (1 ml/kg) into the rats, and after 30 mins, [18F]FDG tracer was applied (i.p. as well). After 30 mins post-injection time, conventional 20 mins long PET/CT acquisitions was performed. After 2 days, the second part was coming, but instead of saline, morphine (1 mg/kg) or methadone (1 mg/kg) was injected i.p. After accessing [18F]FDG, the second PET/CT was conducted as before. For the reconstruction, Teratomo 3D engine was used with attenuation and scatter corrections, with a 0.4 mm resolution.

Figure 4. shows the main results from the PET/CT acquisitions: A. The timeline of the experiment (explained above). B. [18F]FDG uptake after administration of saline (baseline, n = 14), morphine (1 mg/kg, n = 7), or methadone (1 mg/kg, n = 7). Coronal and sagittal images (1.5 mm anterior to bregma and 1.4 mm lateral from the midline, respectively) show the average SUVR calculated using the whole brain as a reference region. C. Voxel-based parametric mapping analyses revealed significantly decreased metabolic activity from baseline values in a basal forebrain region that included the nucleus accumbens and its projecting areas after morphine, but not methadone, treatment. Statistical parametric maps of significant decreases of [18F]FDG uptake (P < 0.05, paired t test). D. and E. VOI analyses of the frontal cortex (FCx), dorsal striatum (DS), and basal forebrain (BF) region, showing a significant differential pattern of [18F]FDG uptake after administration of morphine (D) or methadone (E).

- The authors found significant pharmacodynamic difference between morphine and methadone that is determined entirely by heteromerization of MORs with Gal1Rs, rendering a profound decrease in the potency of methadone. This finding was explained by the weaker proficiency of methadone in activating the dopaminergic system as compared with morphine and predicted a dissociation of the therapeutic and euphoric effects of methadone, which was corroborated by a significantly lower incidence of self-reports of feeling “high” in methadone-medicated patients.

- These results suggest that μ-opioid–Gal1R heteromers mediate the dopaminergic effects of opioids. The results further suggest a lower addictive liability of some opioids, such as methadone, due to their selective low potency for the μ-opioid–Gal1R heteromer.

Nanomedicine and Personalized Treatments

Nanomedicine is simply the medical application of nanotechnologies. The idea is the involvement the use of nanoparticles to improve the behaviour of drug substances. The goal is to achieve improvement over conventional chemotherapies. Customized treatments will be required to overcome the issues raised by clinical patient and disease heterogeneity. As one might expect, the same drug will accumulate in tumors at varying concentrations in patients with different cancers. But this also happens in patients with the same kind of cancer. It has to be ensured that drug nanocarriers are really accumulating in the specific tissues to better treat patients. This brings in the necessity of a treatment prediction tool to select the patients most likely to accumulate high amounts of the nanomedicine of interest and hence benefit from nanomedicinal treatment.

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) is such a noninvasive quantitative imaging tool with excellent sensitivity and spatial/temporal resolution required at the whole-body level. Radiolabeling of liposomal nanomedicines with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) radionuclides has been successfully used to study their biodistribution in preclinical and clinical studies, but SPECT imaging suffers from lower sensitivity and temporal/spatial resolution than PET. However, an ideal PET radiolabeling method viable for both preclinical and clinical imaging wasn’t explored before. Rafael T. M. de Rosales, Alberto Gabizon and colleagues at King’s College London and the Shaare Zedek Medical Center sought to address this challenge.

Edmonds, S. et al. Exploiting the Metal-Chelating Properties of the Drug Cargo for In Vivo Positron Emission Tomography Imaging of Liposomal Nanomedicines. ACS Nano (2016). doi:10.1021/acsnano.6b05935

Edmonds, S. et al. Exploiting the Metal-Chelating Properties of the Drug Cargo for In Vivo Positron Emission Tomography Imaging of Liposomal Nanomedicines. ACS Nano (2016). doi:10.1021/acsnano.6b05935

The following Mediso systems were used to conduct the animal imaging studies: nanoScan PET/CT and NanoSPECT/CT Silver upgrade. Both systems are equipped with the MultiCell animal handling and monitoring system , thus enabling a combined PET-CT/SPECT-CT imaging strategy. Interestingly both PET and SPECT were performed in the same animals (by moving the same bed from scanner from scanner, while the animals were anesthetized in fixed position) that allowed to image the tumour cells with SPECT and the nanomedicine with PET.

Liposomal Drug PET Radiolabeling Method Development

The researchers introduced a simple and efficient PET radiolabeling method exploiting the metal-chelating properties of certain drugs (e.g., bisphosphonates such as alendronate and anthracyclines such as doxorubicin) and widely used ionophores radiolabeled with long half-life metallic PET isotopes, such as 89Zr, 52Mn and 64Cu. The labels — and thus the liposomal drugs — could then be tracked using positron emission tomography (PET) to see where they go within the body. The article discusses in details the feasibility and effectiveness of their method, as well as its advantages and limitations, and show its utility for detecting and quantifying the biodistribution of a liposomal nanomedicine containing an aminobisphosphonate in vivo.

In a model of metastatic breast cancer, the researchers demonstrated that their technique allows quantification of the biodistribution of a radiolabeled stealth liposomal nanomedicine. Alendronate (ALD), an aminobisphosphonate, was selected as the radionuclide-binding drug of choice to develop this method for two reasons: (i) known ability to act as metal chelator to form inert coordination complexes with zirconium, copper, and manganese; and (ii) demonstrated anticancer activity and γ−δ T-cell immunotherapy sensitizing properties. The used liposomal formulation is referred to as PLA in the article.

In a model of metastatic breast cancer, the researchers demonstrated that their technique allows quantification of the biodistribution of a radiolabeled stealth liposomal nanomedicine. Alendronate (ALD), an aminobisphosphonate, was selected as the radionuclide-binding drug of choice to develop this method for two reasons: (i) known ability to act as metal chelator to form inert coordination complexes with zirconium, copper, and manganese; and (ii) demonstrated anticancer activity and γ−δ T-cell immunotherapy sensitizing properties. The used liposomal formulation is referred to as PLA in the article.

Monitoring Liposomal Nanomedicine Distribution

The biodistribution of the radiolabeled liposomes was monitored using PET imaging with 89Zr-PLA in a metastatic mammary carcinoma mouse model established in immunocompromised NSG mice. This cancer model is also traceable by SPECT imaging/fluorescence due to a dual-modality reporter gene, the human sodium iodide symporter (hNIS-tagRFP), that allows sensitive detection of viable cancer tissues (primary tumor and metastases) using SPECT imaging with 99mTc-pertechnetate and fluorescence during dissection and histological studies. The imaging protocol was as follows: first, mice were injected with 89Zr-PLA (4.6 ± 0.4 MBq) at t = 0 followed by nanoScan PET-CT imaging (liposome biodistribution). The same mice were then injected with 99mTc-pertechnetate (30 MBq) and imaged by SPECT-CT. The SPECT injection was repeated at t = 24 h, 72 h, and 168 h. It was confirmed by separate phantom studies that the presence of 99mTc was not affecting the quality/quantification of the PET study. CT images revealed a significant increase in tumor volume during the imaging study. Using the tumor volumes from SPECT and CT, the researchers calculated the percentage of necrotic tumor tissue over time, by subtracting the hNIS-positive volume (SPECT) to the total tumor volume (CT). A PET-CT study was also performed using 64Cu-PLA in an ovarian cancer model (SKOV-3/SCID-Beige) over 48 h to test the versatility and capability of the radiolabeling method.

The common MultiCell animal handling and monitoring system (developed by Mediso) on both imaging systems gave the possibility to easily co-register the PET-CT/SPECT-CT and PET/SPECT studies as the animals were moved in co-registered position between the systems.

MIP video (3D, rotating along z-axis) showing co-registration of PET (red signal, 89Zr-PLA) and SPECT (green signal, 99mTcO4-, hNIS positive viable tumour tissue) of representative tumor from the mutimodal PET/SPECT study in the 3E.Δ.NT/NSG model. Both signals/radiotracers accumulate predominantly at the rim of the tumour and areas of low colocalization as well as high co-localization (yellow) are evident.

Imaging with PET in mouse models of breast and ovarian cancer showed the drugs accumulated in tumors and metastatic tissues in varying concentrations and at levels well above those in normal tissues, the researchers report. In one mouse strain, the nanomedicines unexpectedly showed up in uteruses, a result that wouldn’t have been detected without conducting the imaging study, according to the researchers.

Discussion

The results establish that preformed liposomal nanomedicines, including some currently in clinical use, can be efficiently labeled with PET radiometals and tracked in vivo by exploiting the metal affinity and high concentration of the encapsulated drugs. Importantly, the technique allows radiolabeling of preformed liposomal nanomedicines, without modification of their components and without affecting their physicochemical properties.

The versatility, efficiency, simplicity, and GMP compatibility of this method may enable submicrodosing imaging studies of liposomal nanomedicines containing chelating drugs in humans and may have clinical impact by facilitating the introduction of image-guided therapeutic strategies in current and future nanomedicine clinical studies. The ultimate goal is to use non-invasive imaging data to predict how much drug will be delivered to cancer tissues in specific patients, and whether the nanomedicine is reaching all the patient’s tumors in therapeutic concentrations.

Many thanks for Rafael T. M. de Rosales, the last author of the original article.

Introduction

This post summarizes the results on a research of a new Zr89 PET tracer for cell labeling. The open access article was published last month in the European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging journal:

Charoenphun, P. et al. [89Zr]Oxinate4 for long-term in vivo cell tracking by positron emission tomography. EJNMMI (2014)

The preclinical PET/CT images were acquired on a nanoScan PET/CT in vivo small animal imaging system at King’s College London.

Increasing sensitivity of cell tracking by changing labeling and detection from SPECT to PET

Cell tracking by gamma imaging with radionuclides has been performed clinically for over 30 years and is used for tracking autologous leukocytes to detect sites of infection/inflammation. The standard radiolabelling methodology has been non-specific assimilation of lipophilic, metastable complexes of indium-111 (with oxine) or technetium-99m (with HMPAO). Regenerative medicine and immune cell-based therapies are creating new roles for clinical tracking of these cells. Conventional cell radiolabelling methods have been applied for some of these cell types, but for clinical use new applications will require detection of small lesions and small numbers of cells beyond the sensitivity of traditional gamma camera imaging with In-111 or Tc-99m (e.g. coronary artery disease, diabetes, neurovascular inflammation and thrombus), creating a need for positron-emitting radiolabels to exploit the better sensitivity, quantification and resolution of clinical PET.

So far the search for positron emitting (PET) radiolabels for cells has met with limited success. The near-ubiquitous presence of glucose transporters allows labelling with [18F]-FDG but labelling efficiencies are highly variable, the radiolabel is prone to rapid efflux, and the short half-life (110 min) of F-18 allows only brief tracking. Copper-64 offers a longer (12 h) half-life and efficient cell labelling using lipophilic tracers but rapid efflux of label from cells is a persistent problem and a still longer half-life would be preferred. A “PET analogue” of In-111 oxine, capable of cell tracking over 7 days or more, would be highly desirable but is not yet available.

Zr-89 Oxine: a PET cell radiolabelling agent for long term in vivo cell tracking

This paper describes the first synthesis of Zr-89 oxine, and comparison with In-111 oxine for labelling several cell lines, human leukocytes and tracking of the cancer cell line GFP-5T33 cells in mice. The new lipophilic, metastable complex of Zr-89 can radiolabel a range of cells, independently of specific phenotypes, providing a long-sought solution to the unmet need for a long half-life positron-emitting radiolabel to replace In-111 for cell migration imaging. In addition to the expected advantages (enhanced sensitivity, resolution and quantification) of cell tracking with PET rather than scintigraphy or SPECT, Zr-89 shows less efflux from cells in vitro and in vivo than In-111. GFP-5T33 is a syngeneic murine multiple myeloma model originating from the C57Bl/KaLwRij strain, engineered to express green fluorescent protein (GFP). It was chosen for this work because the fate of the cells after i.v. inoculation is known from the literature. Intravenously injected cells migrate exclusively to the liver, spleen and bone marrow. Furthermore as the radiolabelled cells were GFP positive it was possible to validate the non-invasive images by using flow sorting of the GFP positive cells and negative cells. After flow sorting the authors were able to show that after 7 days in vivo the Zr-89 Oxine cells remained viable for the duration of the study, and that ~95% of radioactivity was present in viable GFP+ cells. The excellent in vivo survival and retention of radioactivity by the cells at 7 days, coupled with the demonstrated ability to acquire useful PET images up to 14 days, significantly extend the typical period over which cells can be tracked by radionuclide imaging with directly labelled cells.

This paper describes the first synthesis of Zr-89 oxine, and comparison with In-111 oxine for labelling several cell lines, human leukocytes and tracking of the cancer cell line GFP-5T33 cells in mice. The new lipophilic, metastable complex of Zr-89 can radiolabel a range of cells, independently of specific phenotypes, providing a long-sought solution to the unmet need for a long half-life positron-emitting radiolabel to replace In-111 for cell migration imaging. In addition to the expected advantages (enhanced sensitivity, resolution and quantification) of cell tracking with PET rather than scintigraphy or SPECT, Zr-89 shows less efflux from cells in vitro and in vivo than In-111. GFP-5T33 is a syngeneic murine multiple myeloma model originating from the C57Bl/KaLwRij strain, engineered to express green fluorescent protein (GFP). It was chosen for this work because the fate of the cells after i.v. inoculation is known from the literature. Intravenously injected cells migrate exclusively to the liver, spleen and bone marrow. Furthermore as the radiolabelled cells were GFP positive it was possible to validate the non-invasive images by using flow sorting of the GFP positive cells and negative cells. After flow sorting the authors were able to show that after 7 days in vivo the Zr-89 Oxine cells remained viable for the duration of the study, and that ~95% of radioactivity was present in viable GFP+ cells. The excellent in vivo survival and retention of radioactivity by the cells at 7 days, coupled with the demonstrated ability to acquire useful PET images up to 14 days, significantly extend the typical period over which cells can be tracked by radionuclide imaging with directly labelled cells.

The use of PET Zr-89 oxine for cell tracking could have a dramatic impact in the investigation of infection, inflammation and cell-based therapies in humans.

In the field of highly sophisticated pre-clinical imaging systems we all know that it’s important to publish articles, technical validations and independent peer reviewed performance evaluation papers on instrumentation. Eventually these performance evaluation, characterization or comparison articles make their way into review articles.

The "review article" is one of the most useful tools available for individuals who need to research a certain topic in the rapidly expanding body of scientific literature. According to Huth [1] a "well-conceived review written after careful and critical assessment of the literature is a valuable document” and it spares time for researchers to keep abreast of all published information. A review article should provide a critical appraisal of the subject.

It is extremely difficult to compare the performance of two imaging systems from different vendors if there is no standardized methodology that is independent of the camera design. Such a methodology should be applicable to a wide range of camera models and geometries. Fortunately for the Primary Investigators there is a NEMA standard publication for performance measurements of small animal positron emission tomographs (NEMA Standards Publication NU 4-2008 [2]) since 2008.

I myself have an engineering background and I’m always astonished how creatively sales people can distort the reality (i.e. numbers) in their marketing materials. I started an excel sheet back in 2007 by filling out numerous specifications for every small animal PET systems, either commercial or academic, when we started the design of our nanoScan small animal PET system at Mediso. Currently it lists about 40 pre-clinical systems including variants (while most of them are now obsolete or discontinued, such as the the Siemens Inveon). As part of my position I closely follow the published performance evaluation and review articles.

Balancing a system design is very delicate question – sensitivity and resolution do not walk hand in hand and it’s easy to get lost in the quagmire of different parameters: ultimately the detector design, the basic parameters and image characteristics together define the image quality. Also the image quality of a certain measurement series does not say anything about reproducibility, long term imaging performance, usability and feature sets.

Review of Review Article

My particular problem with instrumentation review articles is that they usually have a limited/selected subset of parameters which subconsciously (or consciously as I will give the benefit of doubt here) can lead to distortion of the reality. My apologies to the authors of the article by Kuntner & Stout, but this latest review article for preclinical PET imaging and may serve as example [3]. It is a really good article and lists various factors affecting the quantification accuracy of small PET systems. It’s a recommended article to read!

In the first table it shows the characteristics of preclinical PET scanners (visit to the link to view the original table)

The article was published on 28 February 2014, and was originally received on 27 November 2013. It references the Mediso’s microPET system based on an article from JNM 2011 [4]. However the performance evaluation of our next generation nanoScan PET was published online on August 29, 2013 in JNM [5]. Fortunately Spinks and his colleagues published a new paper on the quantitative performance of Albira PET with its largest axial FOV variant in February 2014 [6], so the Albira’s characteristics won’t be distorted – their ‘flagship’ variant is also listed. Lack of access to projection data by the researchers, the standard NEMA procedure could not be used for some of their measurements (e.g. sensitivity, scatter fraction, noise-equivalent counts).

Updated comparison table

So let’s include the updated characteristics in our new table and have a closer look on the parameters.

My problems with the original Table 1 in [3]:

- The ‘ring diameter’ was listed in the comparison table, which is quite non-relevant unless you want disassemble the system. It’s much more useful to list the bore diameter and the transaxial FOV. The bore diameter shows how wide object you can stick into the system, while the transaxial FOV shows that actually where you will collect data from!

- The resolution values listed are not comparable– some of them were listed according to the NEMA NU-4 2008 standard performed with SSRB+FBP (e.g. Inveon), and some of them with iterative reconstruction methods like OSEM (e.g. Genisys4). The pre-clinical PET NEMA standard allows only the usage of the filtered back projection reconstruction method to measure the resolution. More importantly the results have to show the values in all directions: in the transverse slice in radial and tangential directions and additionally the axial resolution shall be measured across transverse slices at 5, 10, 15 and 25 mm radial distances from the center. Example from [5]:

Currently based on the published literature the nanoScan PET subsystem from Mediso delivers the best resolution values for the NEMA NU-4 2008 measurements – even without using the sophisticated 3D Tera-Tomo Reconstruction engine. Based on the original article the reader may derive the false conclusion that the Genisys4 PET delivers the best resolution – while it’s hardly the situation. The FBP recon values had not been published for Genisys4 so far. - The 2D FBP recon provides comparable information on the detector design, but not the system performance! The advanced 3D iterative reconstruction methods allow to incorporate lot of corrections and they provide better spatial resolution, image characteristics – if used properly. Let’s call these resolution values performed by ‘advanced’ reconstruction methods ‘claimed by manufacturer’ values.

- Please always pay attention to the energy window setting when comparing sensitivity values!

Sensitivity

This is general remark for almost all review articles on preclinical PET systems with the exception of JNM article from Goertzen et al [8].

If I’d be interested in the acquisition of a capital equipment, which will be used for at least 10 years, I wanted to see not the peak sensitivity value of the system. This sensitivity is valid usually only in one position – in the radial and transaxial center of the field-of-view. In reality the standard imaged objects are mice, rats and other species, and not point- or line sources. The NEMA standard does contain a method of sensitivity measurement and evaluation for mouse and rat applications which encompass the central 7 cm and 15 cm axial extent. The problem is in practice that these parameters are not listed in the articles for most of the systems – while it’s a really useful value.

In the literature sensitivity values for mouse-sized region are listed only for 3 small animal PET systems: Albira, Inveon and nanoScan. For rat-sized object you can find value only for the Mediso’s system.

The Truth Lies in the Details.

References:

- Edward J. Huth, How to Write and Publish Papers in the Medical Sciences (Williams & Wilkins, 1990).

- National Electrical Manufacturers Association. NEMA Standard Publication NU 4-2008: Performance Measurements of Small Animal Positron Emission Tomographs. Rosslyn, VA: National Electrical Manufacturers Association; 2008

- Claudia Kuntner and David B. Stout, “Quantitative Preclinical PET Imaging: Opportunities and Challenges,” Biomedical Physics 2 (2014): 12, doi:10.3389/fphy.2014.00012. http://journal.frontiersin.org/Journal/10.3389/fphy.2014.00012/full

- Istvan Szanda et al., “National Electrical Manufacturers Association NU-4 Performance Evaluation of the PET Component of the NanoPET/CT Preclinical PET/CT Scanner,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine: Official Publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 52, no. 11 (November 2011): 1741–47, doi:10.2967/jnumed.111.088260. http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/52/11/1741.long

- Kálmán Nagy et al., “Performance Evaluation of the Small-Animal nanoScan PET/MRI System,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine, October 1, 2013, jnumed.112.119065, doi:10.2967/jnumed.112.119065. http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/early/2013/08/26/jnumed.112.119065

- T. J. Spinks et al., “Quantitative PET and SPECT Performance Characteristics of the Albira Trimodal Pre-Clinical Tomograph,” Physics in Medicine and Biology 59, no. 3 (February 7, 2014): 715, doi:10.1088/0031-9155/59/3/715. http://iopscience.iop.org/0031-9155/59/3/715

- Qinan Bao et al., “Performance Evaluation of the Inveon Dedicated PET Preclinical Tomograph Based on the NEMA NU-4 Standards,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 50, no. 3 (2009): 401–8. http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/50/3/401.short

- Andrew L. Goertzen et al., “NEMA NU 4-2008 Comparison of Preclinical PET Imaging Systems,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 53, no. 8 (2012): 1300–1309. http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/53/8/1300.short

- Stephen Adler, Jurgen Seidel, and Peter Choyke, “NEMA and Non-NEMA Performance Evaluation of the Bioscan BioPET/CT Pre-Clinical Small Animal Scanner,” Society of Nuclear Medicine Annual Meeting Abstracts 53, no. Supplement 1 (May 1, 2012): 2402. http://jnumedmtg.snmjournals.org/cgi/content/meeting_abstract/53/1_MeetingAbstracts/2402

- Ken Herrmann et al., “Evaluation of the Genisys4, a Bench-Top Preclinical PET Scanner,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine, July 1, 2013, doi:10.2967/jnumed.112.114926. http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/early/2013/04/29/jnumed.112.114926

- F. Sánchez et al., “Small Animal PET Scanner Based on Monolithic LYSO Crystals: Performance Evaluation,” Medical Physics 39, no. 2 (2012): 643, doi:10.1118/1.3673771. http://link.aip.org/link/MPHYA6/v39/i2/p643/s1&Agg=doi